This article, published today in the New York Times Magazine, is by far one of the strangest pieces about drugs and drug use that I've come across in quite some time.

It genders the drug user - an unnamed academic who succumbed to crack and cocaine in or around 2003 - in that the addict, who was a fit male who could apparently run 5ks in fifteen minutes (like my husband), was an extraordinarily talented and intelligent person who, either because of drugs or through them, had lost his way. His race is unmentioned, though we know that he was heterosexual ("the goal was to meet women"), and the author continually dotes on how skillful and accomplished he was. Unfortunately, the addict "lost his way," and even though his philosophical obsession was the search for happiness (and, seemingly, a search for God), the happiness brought on by the chemicals in crack was an unworthy and lethal substitute for the "real thing."

This is the first of what I'm sure will become many examples of the nostalgic lamentation of lives cut short by drugs. This fit, intelligent, talented young man - able to edit his older colleague's work and even suggest revisions - became "on edge and emotionally needy," a transformation from the idealistic and "chipper" young man he was before. Drugs had clearly cut him down in his prime, and the author obviously "care[s] deeply about him," enough to even write the addict's character letter. In this sense, the piece has some merit: it's true that crack, a drug too often associated only with poor and gritty urban cores, struck down talented academics along with homeless drifting addicts. An article that showcased how even after 1993, people - good, talented, professional people - were succumbing to a drug with America's worst reputation, might have been a way for us to negotiate our views, to realize that crack and cocaine - two powerful addictions - are not only "other people's problems." Maybe this piece could have had some heart. So why does the article end up being all about the author instead? Is it true that when we meet addicts, we prefer to turn their experience into a mirror of our own?

That the article centers more on the author's own experience of the man's addiction rather than the addiction itself is clearly reinforced by the last sentence: "But was I? Maybe there was nothing anyone could do." Here the focus is on the author's experience ("But was I?"), as he questions his own ability to help. But the problem is that he immediately, in the following sentence, diverts himself of any blame by suggesting that there was nothing anyone could do. We're all blameless in this situation; the addict killed himself. The author never mentions that it's fairly rare to die of a crack overdose in 2003. He never mentions that maybe there was more to the situation that a guy who found a false god in cocaine. He also never mentions anything that might bring the situation into perspective; there are no suggestions that maybe there was something we could do.

Instead, this article, like so many more than I'm sure I'll see, briefly examines the abject addict and then quickly looks away to analyze all the more closely the author himself. Addiction is a mirror in which we see our blameless selves. The addict who abandoned a promising academic career for the "false" and "deceitful" gods of crack and cocaine becomes nothing more than a conduit for the author to absolve us all: in his own devolution and death, the addict allows us to look away, be pardoned for not helping since there was "nothing we could do." This failure of happiness is, perhaps, the author's own. After all, the only thing that really seems to matter, in this article at least, is how the author feels about the addiction of someone else.

How American media and popular culture genders drug-involved Americans - and how drug-involved Americans gender themselves.

Sunday, September 11, 2011

Thursday, September 8, 2011

The Government Calls It "Labor Therapy"

A report released Wednesday by the Human Rights Watch (HRW) states that 40,000 Vietnamese drug addicts are currently being held in 123 "rehabilitation centers" across the country, where they are denied actual treatment for their addictions and are forced to work in sweatshop-like conditions, doing things like "process[ing] cashew nuts, sew[ing] garments, and weav[ing] baskets," according to an article the The New York Times released yesterday. Many of these products are then shipped to first-world consumers, often without the knowledge of the company who initially ordered the work. That jacket liners were sewn in detention centers for Columbia Sportswear, for example, was a "surprise" to Peter Bragdon, senior vice president for legal and corporate affairs.

These centers, which the Vietnamese government promote as "labor therapy," were designed after the fall of the South Vietnamese government in 1975 and primarily target heroin addicts as a way to "restore their dignity and learn the value of hard work." They fail on both accounts, however: relapse rates are above 80%, primarily because the only "rehabilitation" the addicts receive are marching in formation and chanting slogans like "Try your best to quit drugs!"

These centers are primarily ways to ensure cheap labor for mass-produced goods without the additional responsibility of actually paying the workers or treating their health concerns. That it happens in Vietnam, particularly within programs designed by the old nationalist/communist government of the North Vietnamese, should perhaps not come as an enormous surprise. That it also happens in the United States should come as a surprise. But it does, and the Human Rights Watch would be wise to turn an eye to addict abuse in America as well.

I've found, in research I've been doing for an upcoming conference paper about teen drug rehabilitation in the United States, that both Teen Challenge houses and a series of Lester Roloff-inspired homes (both in Florida) have been charged with using their young residents to work as groundskeepers, housecleaners, professional 'beggars' (standing outside grocery stores asking for money), and telemarketers, often for payments of less than $.33 a day. The residents - teenagers whose parents enrolled them in these Christian-based rehab centers when their behavior became unacceptable - receive no real drug addiction counseling or rehabilitation. They're instead given the Jesus-based version of the Vietnamese slogan, "Try your best to quit drugs!" And the money they make in these ventures all goes straight back to the rehab centers themselves.

Most of these cases have taken place in states were government intervention in Christian-based enterprises is extremely limited (Texas, Missouri, and Florida, among others), allowing the flagrant abuses of teenagers to take place without any kind of regulation or restriction. These American centers too are designed to 'restore the teens' dignity and teach them the value of hard work.' But again, as in Vietnam, these "rehabilitation centers" fail on both accounts. Instead, the 'Christians' who run these camps profit from the work of innocent children, few of whom ever receive anything close to 'treatment.'

Unpaid labor straight from society's most abject - drug users - is quite clearly a global phenomenon.

These centers, which the Vietnamese government promote as "labor therapy," were designed after the fall of the South Vietnamese government in 1975 and primarily target heroin addicts as a way to "restore their dignity and learn the value of hard work." They fail on both accounts, however: relapse rates are above 80%, primarily because the only "rehabilitation" the addicts receive are marching in formation and chanting slogans like "Try your best to quit drugs!"

These centers are primarily ways to ensure cheap labor for mass-produced goods without the additional responsibility of actually paying the workers or treating their health concerns. That it happens in Vietnam, particularly within programs designed by the old nationalist/communist government of the North Vietnamese, should perhaps not come as an enormous surprise. That it also happens in the United States should come as a surprise. But it does, and the Human Rights Watch would be wise to turn an eye to addict abuse in America as well.

I've found, in research I've been doing for an upcoming conference paper about teen drug rehabilitation in the United States, that both Teen Challenge houses and a series of Lester Roloff-inspired homes (both in Florida) have been charged with using their young residents to work as groundskeepers, housecleaners, professional 'beggars' (standing outside grocery stores asking for money), and telemarketers, often for payments of less than $.33 a day. The residents - teenagers whose parents enrolled them in these Christian-based rehab centers when their behavior became unacceptable - receive no real drug addiction counseling or rehabilitation. They're instead given the Jesus-based version of the Vietnamese slogan, "Try your best to quit drugs!" And the money they make in these ventures all goes straight back to the rehab centers themselves.

Most of these cases have taken place in states were government intervention in Christian-based enterprises is extremely limited (Texas, Missouri, and Florida, among others), allowing the flagrant abuses of teenagers to take place without any kind of regulation or restriction. These American centers too are designed to 'restore the teens' dignity and teach them the value of hard work.' But again, as in Vietnam, these "rehabilitation centers" fail on both accounts. Instead, the 'Christians' who run these camps profit from the work of innocent children, few of whom ever receive anything close to 'treatment.'

Unpaid labor straight from society's most abject - drug users - is quite clearly a global phenomenon.

Tuesday, August 30, 2011

Caught in the Net: The ACLU Examines the Effects of the Drug War on Women

I came across this report late, but it's still an incredible find. The ACLU, along with Break the Chains: Communities of Color and the War on Drugs and the Brennan Center for Justice (housed at my alma mater, NYU), published this report, titled "Caught in the Net: The Impact of Drug Policies on Women and Families," on March 15, 2005. They also organized a two-day conference that same month in order to "begin a national dialogue among lawmakers, social services and criminal justice professionals, and advocates on the impact of drug policies on women and their families." (See here for a link to the letter that uses this language and explains the conference.)

The point of their work, their report, and their conference, was to show that the 'war on drugs' is actually a war on people, and, more specifically, a war on women. As the authors note in their Executive Summary, "Federal and state drug laws and policies over the past twenty years have had specific, devastating, and disparate effects on women, and particularly women of color and low-income women... Women of color use drugs at a rate equal to or lower than white women, yet are far more likely to be affected by current drug laws and policies." These effects have far-reaching consequences, including the mass incarceration of eight times the amount of women who were incarcerated in 1980, widespread cases of sexual and physical violence and abuse among women who are incarcerated, heightened levels of psychological and physical trauma among this same population, and the rippling effects of displaced and poverty-stricken children due to incarcerated mothers, fathers, and parents.

I highly recommend the report, particularly for its hard and cold facts regarding populations that we don't consider highly involved in American drug policies or our current drug war. This report highlights the often-hidden (or purposefully disguised) victims of on ongoing irrational policies. While it mentions very little about the media's role in influencing the ways we view drug-involved women, it's nonetheless a useful report, and certainly a step in the right direction.

What I haven't been able to find is any additional information about Break the Chains (the only thing I see is an anti-oppression organization from by a Women's Baptist Association). Is this organization no longer around? Does anyone have any additional information on it?

The point of their work, their report, and their conference, was to show that the 'war on drugs' is actually a war on people, and, more specifically, a war on women. As the authors note in their Executive Summary, "Federal and state drug laws and policies over the past twenty years have had specific, devastating, and disparate effects on women, and particularly women of color and low-income women... Women of color use drugs at a rate equal to or lower than white women, yet are far more likely to be affected by current drug laws and policies." These effects have far-reaching consequences, including the mass incarceration of eight times the amount of women who were incarcerated in 1980, widespread cases of sexual and physical violence and abuse among women who are incarcerated, heightened levels of psychological and physical trauma among this same population, and the rippling effects of displaced and poverty-stricken children due to incarcerated mothers, fathers, and parents.

I highly recommend the report, particularly for its hard and cold facts regarding populations that we don't consider highly involved in American drug policies or our current drug war. This report highlights the often-hidden (or purposefully disguised) victims of on ongoing irrational policies. While it mentions very little about the media's role in influencing the ways we view drug-involved women, it's nonetheless a useful report, and certainly a step in the right direction.

What I haven't been able to find is any additional information about Break the Chains (the only thing I see is an anti-oppression organization from by a Women's Baptist Association). Is this organization no longer around? Does anyone have any additional information on it?

Wednesday, August 17, 2011

The Women of 'The Cross and the Switchblade' (film version), 1970: Bo

I recently had a chance to watch The Cross and the Switchblade, the 1970 film adaptation of Reverend David Wilkerson's 1962 memoir of the same name. The story takes place in 1958, when Wilkerson, a young pastor from rural Pennsylvania (Philipsburg, PA, about 190 miles from Allentown, my hometown) is led by God on a mission to bring salvation to the young boys and girls who make up some of Bedford-Stuyvesant's most notorious gangs. He is particularly taken, in the book as well as the film, by the case of Nicky Cruz, the most violent (and most deeply troubled) member of the Mau Maus, a Latino gang who is tied in a tight rivalry with the Bishops, a gang of African American youths.

(And yes, it's really true that the Puerto Rican gang is named the Mau Maus rather than the African American gang, even though the source of the gang's name, the anticolonial Mau Mau rebellion in Kenya which took place between 1952 and 1960, has an obvious and distinctive African connotation.)

While it is the story of the conversion of Nicky Cruz that lies at the The Cross and the Switchblade's center, both the book and the film take on issues of drug use, sexuality, race and gender at length (even if they texts don't do so on purpose), and the film in particular constantly tangles with issues of drug-involved womanhood and notions of 'proper' femininity. While the whole story of The Cross and the Switchblade, along with Wilkerson's eventual leadership of the Times Square Church and his founding of Teen Challenge International and World Challenge ministries, are crucial elements of the larger David Wilkerson mythos, I don't have the time or space to deal with these here. (See, instead, my upcoming paper at the American Historical Association's annual meeting in January - a link will be provided here soon.) Instead, I will focus on the ways in which drug-involved womanhood is represented in the 1970 film, and the ways in which religion and drug use mold these ongoing cinematic conversations.

The film ostensibly focuses on and celebrates the homosocial conversion of the manly warlord Nicky Cruz, whose manhood (as showcased by violent behavior and heteronormative sexual relationships) is never doubted (even though the film has an extended - and deeply homoerotic - scene in which Wilkerson arrives at Nicky's apartment at 3 a.m. to tell him that "God loves him," while Nicky is shown only in his underwear, and in small white briefs at that). Nonetheless, it is the concurrent conversions of Rosa and Bo - conversions both to Protestant Christianity and to more traditional notions of performative femininity - that prove both the 'healing' power of Protestant Christian belief and the beneficial attributes of performing (bodily, spiritually, sartorially) traditional womanhood. Though they're hardly as celebrated as Nicky Cruz, in the film version, the female characters of Rosa and Little Bo Peep (referred to as Bo throughout the film) play enormously important roles in Wilkerson's story of evangelical success. This posting will focus specifically on Bo, with an examination of Rosa (or Maria, as she's known in the book version) following at a later time.

In her first scene, only six minutes into the film, Bo proudly tells Wilkerson of her shortened femininzed nickname: Little Bo Peep, the sweet fairy tale sheperdess, becomes the more masculine, or at least androgynous, 'Bo.' She is a young African American girl who proudly "runs alone," doesn't do drugs ("I ain't got no use for jitterbuggin' or gettin' messed up") and serves as Wilkerson's first introduction to gang life in New York. As a 'messenger,' unaffiliated with any specific gang but able to transport messages between them, Bo is able to enter territory that would be off-limits to others. In many ways, her liminal status (unaffiliated with any one group, often working alone) is repeated in many ways: in her spiritual indifference, her lack of alignments, and, most notably, in her androgyny.

From the moment we first see Bo (a character who is not present in the 1962 text), the audience is unsure if she is a boy or a girl. She's dressed in jeans, a loose leather coat, a sweater, and a ragged hat: clothing that provides no clear gender markers. She even refers to her androgynous, liminal state a bit later in the film. As she and Wilkerson walk through the streets of Brooklyn, Bo pulls a trumpet out of an unlocked car and begins to play it, lamenting that she "used to play in the YMCA Drum and Bugle corps until they kicked [her] out." "Why'd they kick you out?" asks David Wilkerson, as played by Pat Boone. "Found out I was a girl," Bo answers. To this, Wilkerson smiles. Bo casts her eyes down, briefly, and we see a flicker of shame on her face. She then places the trumpet back into the unlocked car.

Bo instantly aligns herself with Wilkerson, an alignment that marks the first of Bo's transitions from liminal figure into a gendered, feminized, 'proper' Christian girl. Other transitions soon follow. Wilkerson and Bo are both taken in by a large heteronormative family, the Gomezes, which allows Bo to live with a 'proper' Christian family for the first time of her life. She also begins working with Wilkerson on the large 'youth rally' that he is organizing to unite the gangs and bring all of them together to be 'saved.' That all of these changes take place in the vicinity of a church comes as no huge surprise: Hector Gomez, the patriarch of his family, is also the pastor of a small urban Christian church (the sanctuary of which is located directly off of the family's kitchen), and it is his family that quickly takes Bo and Wilkerson under their collective wing.

In many ways, this scene is charming, a vision of racial unity amongst the backdrop of racially-charged gang tensions. But it also speaks to Bo's decreasing liminality. Prior to her alignment with Wilkerson, Bo was seen only with her friend Bottle Cap, another African American youth. Now, she's suddenly the right-hand woman of a white pastor from rural PA and living in domestic tranquility with a family of Latinos. She is no longer adrift and living in the streets; instead, she is anchored into a multi-racial family, all of whom are committed to drug-free Christian ideals and working for the benefit and redemption of others. For a short film (less than two hours) that deals extensively with drug use and gang violence, Bo can be read as one of the film's biggest successes, particularly at the end when she works at Wilkerson's youth rally, and we see Bo dramatically transformed.

The rally, which takes place in a large theater (gesturing towards Wilkerson's future pastorship at the Times Square Church in a renovated Broadway theater), is the last, and most dramatic, scene in the film. Naturally, the bulk of the action focuses on Nicky's acceptance of Christian doctrine and his affirmation of his newfound belief. But prior to the arrival of the gangs, we also see a marked transformation that is physical, sartorial, and social: Bo, wearing a skirt and fitted sweater, along with knee socks and loafers. Gone are the jeans and the beat-up hat. Instead, she is carrying a stack of small Bibles before the rally begins. She helps set up the pulpit on the stage, helping the Gomezes set up stacks of Bibles, and then she is never seen or heard from again. The film ends shortly thereafter, after the gangs arrive, rumble a bit, Wilkerson preaches and Nicky repents, but we never again see Bo on screen.

It seems that Bo, who does not battle a drug addiction in the film (that's the role of Rosa/Maria - more on that in the next post - but Bo does know where, how, and when the drugs are being used, sold, etc, which makes her drug-involved enough for consideration here), is completed as a character by the time she reaches the rally and has a fully social and sartorial conversion. It's unnecessary for us as an audience to see her religious conversion (one may assume that, through her alliance with Wilkerson and her help with the rally, this has already taken place). Instead, what adherence to Protestantism has brought for Bo is a conversion in the realm of social comportment: now that she has accepted Christ, she conforms to traditional notions of femininity as well. This can be seen in her skirt and her knee socks, her docile and subservient nature (carrying Bibles, helping set up the rally), and, ultimately, the fact that her conversion warrants very little screen time. For a character that Wilkerson relies upon completely to find and meet the gangs he hopes to aid, Bo's conversion is wordless, unremarked-upon, completely visual, and finalized when she wears a skirt instead of jeans. She is the ultimate subservient woman, letting the man's conversion (Nicky's) take the cake. We as an audience don't know if she also assumes a more feminized name, but we can rest assured that, since Bo has found both God and a skirt, her conversion to traditional ideas of Protestant Christianity and traditional womanhood is complete.

Finally, the fact that this character has no duplicate in the text assures us as a film-watching audience that Bo's visual sartorial conversion is sufficient for us to understand that she is, indeed, changed. The book traces no such similar account - there is no young ragamuffin in the book who drops her jeans for skirts when she begins to follow Christ's word. Bo's presence in the film (a catalyst to help Wilkerson find the gangs, a visual confirmation of the transformative power of Christianity) is, in many ways, a completely optical experience, much like the process of film-watching itself. In this sense, Bo both reminds and proves to us, a movie-watching audience, the visual power that comes with images on screen. Bo's role, while minimal, is also complete: Rosa/Maria needs to get over her heroin addiction before she can be saved, and Nicky needs to leave gang-life behind. But Bo? She can put on some knee socks and a skirt and we, the audience, can see all we need to know.

More on Rosa/Maria next time...

(And yes, it's really true that the Puerto Rican gang is named the Mau Maus rather than the African American gang, even though the source of the gang's name, the anticolonial Mau Mau rebellion in Kenya which took place between 1952 and 1960, has an obvious and distinctive African connotation.)

While it is the story of the conversion of Nicky Cruz that lies at the The Cross and the Switchblade's center, both the book and the film take on issues of drug use, sexuality, race and gender at length (even if they texts don't do so on purpose), and the film in particular constantly tangles with issues of drug-involved womanhood and notions of 'proper' femininity. While the whole story of The Cross and the Switchblade, along with Wilkerson's eventual leadership of the Times Square Church and his founding of Teen Challenge International and World Challenge ministries, are crucial elements of the larger David Wilkerson mythos, I don't have the time or space to deal with these here. (See, instead, my upcoming paper at the American Historical Association's annual meeting in January - a link will be provided here soon.) Instead, I will focus on the ways in which drug-involved womanhood is represented in the 1970 film, and the ways in which religion and drug use mold these ongoing cinematic conversations.

The film ostensibly focuses on and celebrates the homosocial conversion of the manly warlord Nicky Cruz, whose manhood (as showcased by violent behavior and heteronormative sexual relationships) is never doubted (even though the film has an extended - and deeply homoerotic - scene in which Wilkerson arrives at Nicky's apartment at 3 a.m. to tell him that "God loves him," while Nicky is shown only in his underwear, and in small white briefs at that). Nonetheless, it is the concurrent conversions of Rosa and Bo - conversions both to Protestant Christianity and to more traditional notions of performative femininity - that prove both the 'healing' power of Protestant Christian belief and the beneficial attributes of performing (bodily, spiritually, sartorially) traditional womanhood. Though they're hardly as celebrated as Nicky Cruz, in the film version, the female characters of Rosa and Little Bo Peep (referred to as Bo throughout the film) play enormously important roles in Wilkerson's story of evangelical success. This posting will focus specifically on Bo, with an examination of Rosa (or Maria, as she's known in the book version) following at a later time.

In her first scene, only six minutes into the film, Bo proudly tells Wilkerson of her shortened femininzed nickname: Little Bo Peep, the sweet fairy tale sheperdess, becomes the more masculine, or at least androgynous, 'Bo.' She is a young African American girl who proudly "runs alone," doesn't do drugs ("I ain't got no use for jitterbuggin' or gettin' messed up") and serves as Wilkerson's first introduction to gang life in New York. As a 'messenger,' unaffiliated with any specific gang but able to transport messages between them, Bo is able to enter territory that would be off-limits to others. In many ways, her liminal status (unaffiliated with any one group, often working alone) is repeated in many ways: in her spiritual indifference, her lack of alignments, and, most notably, in her androgyny.

From the moment we first see Bo (a character who is not present in the 1962 text), the audience is unsure if she is a boy or a girl. She's dressed in jeans, a loose leather coat, a sweater, and a ragged hat: clothing that provides no clear gender markers. She even refers to her androgynous, liminal state a bit later in the film. As she and Wilkerson walk through the streets of Brooklyn, Bo pulls a trumpet out of an unlocked car and begins to play it, lamenting that she "used to play in the YMCA Drum and Bugle corps until they kicked [her] out." "Why'd they kick you out?" asks David Wilkerson, as played by Pat Boone. "Found out I was a girl," Bo answers. To this, Wilkerson smiles. Bo casts her eyes down, briefly, and we see a flicker of shame on her face. She then places the trumpet back into the unlocked car.

Bo instantly aligns herself with Wilkerson, an alignment that marks the first of Bo's transitions from liminal figure into a gendered, feminized, 'proper' Christian girl. Other transitions soon follow. Wilkerson and Bo are both taken in by a large heteronormative family, the Gomezes, which allows Bo to live with a 'proper' Christian family for the first time of her life. She also begins working with Wilkerson on the large 'youth rally' that he is organizing to unite the gangs and bring all of them together to be 'saved.' That all of these changes take place in the vicinity of a church comes as no huge surprise: Hector Gomez, the patriarch of his family, is also the pastor of a small urban Christian church (the sanctuary of which is located directly off of the family's kitchen), and it is his family that quickly takes Bo and Wilkerson under their collective wing.

In many ways, this scene is charming, a vision of racial unity amongst the backdrop of racially-charged gang tensions. But it also speaks to Bo's decreasing liminality. Prior to her alignment with Wilkerson, Bo was seen only with her friend Bottle Cap, another African American youth. Now, she's suddenly the right-hand woman of a white pastor from rural PA and living in domestic tranquility with a family of Latinos. She is no longer adrift and living in the streets; instead, she is anchored into a multi-racial family, all of whom are committed to drug-free Christian ideals and working for the benefit and redemption of others. For a short film (less than two hours) that deals extensively with drug use and gang violence, Bo can be read as one of the film's biggest successes, particularly at the end when she works at Wilkerson's youth rally, and we see Bo dramatically transformed.

The rally, which takes place in a large theater (gesturing towards Wilkerson's future pastorship at the Times Square Church in a renovated Broadway theater), is the last, and most dramatic, scene in the film. Naturally, the bulk of the action focuses on Nicky's acceptance of Christian doctrine and his affirmation of his newfound belief. But prior to the arrival of the gangs, we also see a marked transformation that is physical, sartorial, and social: Bo, wearing a skirt and fitted sweater, along with knee socks and loafers. Gone are the jeans and the beat-up hat. Instead, she is carrying a stack of small Bibles before the rally begins. She helps set up the pulpit on the stage, helping the Gomezes set up stacks of Bibles, and then she is never seen or heard from again. The film ends shortly thereafter, after the gangs arrive, rumble a bit, Wilkerson preaches and Nicky repents, but we never again see Bo on screen.

It seems that Bo, who does not battle a drug addiction in the film (that's the role of Rosa/Maria - more on that in the next post - but Bo does know where, how, and when the drugs are being used, sold, etc, which makes her drug-involved enough for consideration here), is completed as a character by the time she reaches the rally and has a fully social and sartorial conversion. It's unnecessary for us as an audience to see her religious conversion (one may assume that, through her alliance with Wilkerson and her help with the rally, this has already taken place). Instead, what adherence to Protestantism has brought for Bo is a conversion in the realm of social comportment: now that she has accepted Christ, she conforms to traditional notions of femininity as well. This can be seen in her skirt and her knee socks, her docile and subservient nature (carrying Bibles, helping set up the rally), and, ultimately, the fact that her conversion warrants very little screen time. For a character that Wilkerson relies upon completely to find and meet the gangs he hopes to aid, Bo's conversion is wordless, unremarked-upon, completely visual, and finalized when she wears a skirt instead of jeans. She is the ultimate subservient woman, letting the man's conversion (Nicky's) take the cake. We as an audience don't know if she also assumes a more feminized name, but we can rest assured that, since Bo has found both God and a skirt, her conversion to traditional ideas of Protestant Christianity and traditional womanhood is complete.

Finally, the fact that this character has no duplicate in the text assures us as a film-watching audience that Bo's visual sartorial conversion is sufficient for us to understand that she is, indeed, changed. The book traces no such similar account - there is no young ragamuffin in the book who drops her jeans for skirts when she begins to follow Christ's word. Bo's presence in the film (a catalyst to help Wilkerson find the gangs, a visual confirmation of the transformative power of Christianity) is, in many ways, a completely optical experience, much like the process of film-watching itself. In this sense, Bo both reminds and proves to us, a movie-watching audience, the visual power that comes with images on screen. Bo's role, while minimal, is also complete: Rosa/Maria needs to get over her heroin addiction before she can be saved, and Nicky needs to leave gang-life behind. But Bo? She can put on some knee socks and a skirt and we, the audience, can see all we need to know.

More on Rosa/Maria next time...

Friday, August 12, 2011

Kitty McNeil, "The Babbling Bodhisattva"

In his introduction to the collected San Francisco Oracle archives, Allen Cohen wrote that Kitty McNeil, "a suburban housewife, theosophist of the Alice Bailey variety, a psychic, and a lover of LSD and hippies," wrote to Oracle columnist Carl Helbing, an artist and astrologer who lived in the Haight, to answer his previously-published astrological query, 'Who then can tell us further of Him who was born on February 5, 1962, when 7 planets were in Aquarius?' McNeil's response was "a joint meditation on the inner planes with all the world's adepts providing the spiritual energy and will needed to bring about the birth of the next avatar." Pretty heavy stuff for 'a suburban housewife,' even if she is a psychic and a lover of LSD.

Cohen doesn't quote any of her letter itself, nor does he mention Helbing's response. There's no other real information about McNeil at all - no mention of where she lived or how she learned about astrology, or even if she stayed in touch with the paper. Cohen only suggests that he and the rest of the Oracle staff immediately made McNeil into a 'columnist' and her article 'The Babbling Bodhissatva' was born, but this is somewhat false. McNeil's column, which was published anonymously, appears only once in the twelve-paper, two-year run of the Oracle, on pages 5, 35, and 39 of Oracle #7, "The Houseboat Summit," which was published in April of 1967. 'The Babbling Bodhissatva' never appears in the Oracle again.

McNeil's article is luminous - well-written, engaging, spiritually and astrologically rich. Subtitled 'The Advent of the World-Teacher,' McNeil wrote about "the descent of the Christos, the archetypal Christ of the astral plane," which would herald "an important step in preparation for manifestation in the world of men." But she does not immediately suggest that a new divine being has come to Earth to show humankind the way. Instead, she argues that "it is only our own spiritual ignorance and lack of entire enlightenment that does not recognize the latent spiritual process that brings forth the immanent Divinity within every man and woman." In other words, the great astrological descent of 'Christ' is, in reality, a personal process of mass spiritual awakening.

She quotes from the work of Evelyn Underhill, Alice Bailey, and Jacob Boehme to make her point, arguing that other scholars familiar with history have suggested similar things. But, ultimately, "whether we call this manifestation and Incarnation of Christ, Vishnu, Ishvara, or Krishna, it is the indwelling Divinity made manifest in flesh" that matters, and that people have sought (and followed) these avatars for thousands of years. These avatars arrive in accordance with astrological cycles of divine energy, but this new avatar "will have none of these names. He may go unrecognized, as men are blinded by the glamours of the past." The Age of Aquarius is, for McNeil, very real. It presents the world with "the cosmic energies that will bring forth the emergence of the World Teacher with his Spiritual Hierarchy of helpers who will awake, one by one, to their true role."

We all have "the Grace of embodiment of the White Light," says McNeil, "the Atman become Brahmin [which is] in purest form in the Great Ones, the guides of the race, but also in you and you and you." She then goes on to present the "Collabria" as a "liberating new term and model... which we think can melt some thought-barriers for humanity." It "implies unified working together on all levels of awareness to purity, broaden and harmonize the interacting energy-field streaming through our lives." Though she admits it will take some work to accomplish, "the Collabria is all of us plus the world of spiritual forces, and is here and now... You are the Collabria and so am I. Let's act like it - - - whatever that means. May you find the vision to give it glory, beauty and Light. I need it."

I am incredibly interested in McNeil as a writer, a woman, and an artist, and I greatly desire to know more about her. In the few searches I've done I've found nothing on her, and I have very little information to go on. If anyone has any information about Kitty McNeil, the Babbling Bodhissatva, please send it my way. I'd love to know more about this fascinating woman.

Thursday, August 11, 2011

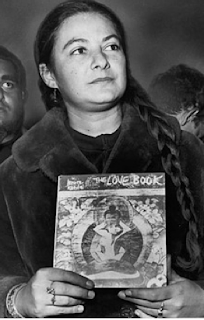

Lenore Kandel (1932-2009)

“When a society is afraid of its poets, it is afraid of itself. A society afraid of itself stands as another definition of hell.” – Lenore Kandel

Lenore Kandel, who died in San Francisco in 2009 at the age of 77 from complications of lung cancer, was an uncommon woman in both the Beat and hippie countercultures. A peer and a participant rather than a girlfriend or a muse, Kandel was one of the strongest, most poetic, and perhaps the most frankly sexual voice of the female experience of San Francisco in the 1960s. Though she published only two books of poetry during her lifetime and was virtually unheard of for nearly thirty years preceding her death, her small body of work attracted both critical and popular acclaim as well as wide-ranging legal ramifications (an obscenity charge against her 1966 publication The Love Book became the longest-running case in San Francisco court history). Nonetheless, a thorough understanding of the artistic movement of the 1960s is simply incomplete without considering her poetic, political, and psychedelic submissions. Lenore Kandel was a pioneer, challenging conventions in the realms of female artistry, literature, and the fight against censorship. The countercultural canon is incomplete without her.

Born in 1932 in New York City, she was an infant when Kandel moved with her family to Los Angeles where her father was a Hollywood screenwriter. She was already a student of poetry, Zen, and belly dancing by the time she moved to San Francisco in 1960, where she remained for the rest of her life. Through her work, her feminism, her radical and avant-garde politics, her belief in the powerful psychedelic potential of the counterculture, and her longtime residence in San Francisco, Kandel was a bridge between the Beats of the 1950s and the burgeoning California hippie movement of the 1960s. Upon arriving in San Francisco, Kandel fell in with the poets Lew Welch and Gary Snyder, and had a brief affair with Jack Kerouac. (Kerouac used her as a model for Romana Swartz in his 1962 novel Big Sur.) She spent time at the East-West House, the San Francisco writer's cooperative, read at a University of California Poetry Conference in November of 1964, and played a pot-smoking Deaconess in the 1969 Kenneth Anger film Invocation of My Demon Brother. In 1966, the same year she published The Love Book, Kandel became involved with the Diggers, which solidified her belief in the power of "community anarchy" as she worked with the group to provide free food and medical care, along with consciousness raising musical events.

The Love Book, her best known work, was only four poems and eight pages long, but its “holy erotica” (her term for her erotically charged free verse celebrating the divine nature of loving and supernal sexuality she became best known for) was deemed transgressive enough for newly-elected governor Ronald Reagan to authorize a police raid on the two San Francisco bookstores (City Lights and the Psychedelic Shop) that sold it, signaling the new governor’s first attack on the growing psychedelic counterculture that was forming in his state. The Love Book was banned on violation of California’s obscenity codes shortly after it was published, and its trial became the longest-running in San Francisco’s history, as it made its way all the way up to the California Supreme Court (the prosecution was finally overturned in 1974). Writing in the San Francisco Oracle after the bookstores' bust, Lenore described The Love Book as being about "the invocation, recognition and acceptance of the divinity in man thru the medium of physical love." She also refused to acknowledge the validity of Reagan's belief in censorship as a means to protect the moral wellbeing of Californian society, insisting instead that it did more harm than good: "Any form of censorship, whether mental, moral, emotional or physical, whether from the inside or the outside in, is a barrier against self-awareness."

Her prominent role in the hippie counterculture reached its apotheosis when she was the only female speaker at the Human Be-In on January 14, 1967. In a coincidence the Zen student undoubtedly enjoyed, January 14th also happened to be her 35th birthday. The crowd of roughly 25,000 sang 'Happy Birthday' to her after she read selections from The Love Book and declared that the god of the dawning new age was Love. Kandel's act, as well as the entire gathering, was in defiance of many of California's new laws that specifically targeted the growing counterculture. Kandel's book had been banned on violation of obscenity codes in November of 1966, just a month after the psychotropic drug fueling much of the entire movement, LSD, was formally outlawed in California (on October 6, 1966).

In 1967, Kandel published her first full-length (and final) collection of poems, entitled Word Alchemy, that featured many of the same themes as The Love Book. In To Fuck With Love Phase III, a poem that continues a piece first featured in The Love Book, she wrote:

"I have whispered love into every orifice of your body

As you have done

to me

my whole body is turning into a cuntmouth

my toes my hands my belly my breast my shoulder my eyes

you fuck me continually with your tongue you look

with your words with your presence

we are transmuting

we are as soft and warm and trembling

as a new gold butterfly

the energy

indescribable

almost unendurable

at night sometimes i see our bodies glow"

In 1970 Kandel and her lover Bill Fritsch, a poet and a Hell's Angel, were involved in a serious motorcycle crash that ruined her spine and left her permanently disabled. Both she and her work faded from the spotlight, though there was a renewed interest in her work in the early 2000s when she spoke at the 40th anniversary of the Human Be-In in 2007. Because of her long silence, her work has been eclipsed by other, generally male, poets who have come to define both the Beat and hippie eras, but a new publication of her collected work is slated for publication in 2012.

Her importance to the movements of the 1960s and for the artistry of the era cannot be overstated, however. As Ronna C. Johnson wrote in her essay, "Lenore Kandel's The Love Book: Psychedelic Poetics, Cosmic Erotica, and Sexual Politics in the Mid-sixties Counterculture" (from Reconstructing the Beats, Jennie Skerl, ed. [Palgrave Macmillan, 2004]), "As the poet Lenore Kandel saliently attests, women writers were radical exponents of Beat and San Francisco Renaissance poetics; at times also flouting censorship codes, they advanced the cultural reforms and oppositions the movements engaged. Moreover, challenging conventions about female passivity, sexual equality, and subjectivity, women's avant-garde literary departures established the proto-feminist dimensions of Beat... Kandel elucidated the incipient feminism linking Beat to hippie ethics and aesthetics." (89-90)

Kandel, for her many artistic and social contributions, deserves both our recognition and remembrance.

Lenore Kandel, who died in San Francisco in 2009 at the age of 77 from complications of lung cancer, was an uncommon woman in both the Beat and hippie countercultures. A peer and a participant rather than a girlfriend or a muse, Kandel was one of the strongest, most poetic, and perhaps the most frankly sexual voice of the female experience of San Francisco in the 1960s. Though she published only two books of poetry during her lifetime and was virtually unheard of for nearly thirty years preceding her death, her small body of work attracted both critical and popular acclaim as well as wide-ranging legal ramifications (an obscenity charge against her 1966 publication The Love Book became the longest-running case in San Francisco court history). Nonetheless, a thorough understanding of the artistic movement of the 1960s is simply incomplete without considering her poetic, political, and psychedelic submissions. Lenore Kandel was a pioneer, challenging conventions in the realms of female artistry, literature, and the fight against censorship. The countercultural canon is incomplete without her.

Born in 1932 in New York City, she was an infant when Kandel moved with her family to Los Angeles where her father was a Hollywood screenwriter. She was already a student of poetry, Zen, and belly dancing by the time she moved to San Francisco in 1960, where she remained for the rest of her life. Through her work, her feminism, her radical and avant-garde politics, her belief in the powerful psychedelic potential of the counterculture, and her longtime residence in San Francisco, Kandel was a bridge between the Beats of the 1950s and the burgeoning California hippie movement of the 1960s. Upon arriving in San Francisco, Kandel fell in with the poets Lew Welch and Gary Snyder, and had a brief affair with Jack Kerouac. (Kerouac used her as a model for Romana Swartz in his 1962 novel Big Sur.) She spent time at the East-West House, the San Francisco writer's cooperative, read at a University of California Poetry Conference in November of 1964, and played a pot-smoking Deaconess in the 1969 Kenneth Anger film Invocation of My Demon Brother. In 1966, the same year she published The Love Book, Kandel became involved with the Diggers, which solidified her belief in the power of "community anarchy" as she worked with the group to provide free food and medical care, along with consciousness raising musical events.

The Love Book, her best known work, was only four poems and eight pages long, but its “holy erotica” (her term for her erotically charged free verse celebrating the divine nature of loving and supernal sexuality she became best known for) was deemed transgressive enough for newly-elected governor Ronald Reagan to authorize a police raid on the two San Francisco bookstores (City Lights and the Psychedelic Shop) that sold it, signaling the new governor’s first attack on the growing psychedelic counterculture that was forming in his state. The Love Book was banned on violation of California’s obscenity codes shortly after it was published, and its trial became the longest-running in San Francisco’s history, as it made its way all the way up to the California Supreme Court (the prosecution was finally overturned in 1974). Writing in the San Francisco Oracle after the bookstores' bust, Lenore described The Love Book as being about "the invocation, recognition and acceptance of the divinity in man thru the medium of physical love." She also refused to acknowledge the validity of Reagan's belief in censorship as a means to protect the moral wellbeing of Californian society, insisting instead that it did more harm than good: "Any form of censorship, whether mental, moral, emotional or physical, whether from the inside or the outside in, is a barrier against self-awareness."

Her prominent role in the hippie counterculture reached its apotheosis when she was the only female speaker at the Human Be-In on January 14, 1967. In a coincidence the Zen student undoubtedly enjoyed, January 14th also happened to be her 35th birthday. The crowd of roughly 25,000 sang 'Happy Birthday' to her after she read selections from The Love Book and declared that the god of the dawning new age was Love. Kandel's act, as well as the entire gathering, was in defiance of many of California's new laws that specifically targeted the growing counterculture. Kandel's book had been banned on violation of obscenity codes in November of 1966, just a month after the psychotropic drug fueling much of the entire movement, LSD, was formally outlawed in California (on October 6, 1966).

In 1967, Kandel published her first full-length (and final) collection of poems, entitled Word Alchemy, that featured many of the same themes as The Love Book. In To Fuck With Love Phase III, a poem that continues a piece first featured in The Love Book, she wrote:

"I have whispered love into every orifice of your body

As you have done

to me

my whole body is turning into a cuntmouth

my toes my hands my belly my breast my shoulder my eyes

you fuck me continually with your tongue you look

with your words with your presence

we are transmuting

we are as soft and warm and trembling

as a new gold butterfly

the energy

indescribable

almost unendurable

at night sometimes i see our bodies glow"

In 1970 Kandel and her lover Bill Fritsch, a poet and a Hell's Angel, were involved in a serious motorcycle crash that ruined her spine and left her permanently disabled. Both she and her work faded from the spotlight, though there was a renewed interest in her work in the early 2000s when she spoke at the 40th anniversary of the Human Be-In in 2007. Because of her long silence, her work has been eclipsed by other, generally male, poets who have come to define both the Beat and hippie eras, but a new publication of her collected work is slated for publication in 2012.

Her importance to the movements of the 1960s and for the artistry of the era cannot be overstated, however. As Ronna C. Johnson wrote in her essay, "Lenore Kandel's The Love Book: Psychedelic Poetics, Cosmic Erotica, and Sexual Politics in the Mid-sixties Counterculture" (from Reconstructing the Beats, Jennie Skerl, ed. [Palgrave Macmillan, 2004]), "As the poet Lenore Kandel saliently attests, women writers were radical exponents of Beat and San Francisco Renaissance poetics; at times also flouting censorship codes, they advanced the cultural reforms and oppositions the movements engaged. Moreover, challenging conventions about female passivity, sexual equality, and subjectivity, women's avant-garde literary departures established the proto-feminist dimensions of Beat... Kandel elucidated the incipient feminism linking Beat to hippie ethics and aesthetics." (89-90)

Kandel, for her many artistic and social contributions, deserves both our recognition and remembrance.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)